Check out my website at www.williamhillyard.com

Check out my website at www.williamhillyard.com

Website: www.williamhillyard.com

13 Jul 2011 Leave a comment

by William Hillyard in Uncategorized

Sarah Palin’s Drive-Thru Alaska

30 Nov 2010 Leave a comment

by William Hillyard in Published Stories Tags: Alaska, anchorage, Bill Hillyard, blight, Denali, fast food, Literary Journalism, Mount McKinley, open for business, Sarah Palin, sprawl, suburbia, Talkeetna, walmart, Wasilla, William Hillyard

One November morning, several years ago, I set out from Anchorage, Alaska heading north to a place where I heard I could catch a glimpse of Mount McKinley. In late autumn in Alaska dawn breaks mid-morning and on that particular day its weak rays offered nothing more than a feeble fluorescent glow through heavy clouds. The sky buried the mountains in featureless gray pressing down on a scabby landscape the color of mud. It wanted to rain.

To get out of Anchorage, to head north, you must pass through Wasilla, that Wasilla, Sarah Palin’s hometown. I remember it as a smear of tin buildings and soulless strip malls strewn along the highway across open ditches. The franchise fast food and gas stations were interleaved with brambly thickets of stunted trees. Decaying cars marked the entrances to dirt tracks tunneling into the marshy brush.

Sarah Palin had proclaimed the city “open for business,” cheering on the corporate big-box economy and fueling indiscriminate growth. Driving through Wasilla these days, a town of about eight thousand, you’ll pass two McDonalds, a Burger King, a Wendy’s, an Arby’s, Taco Bell, KFC, Carl’s Jr., Pizza Hut, Dairy Queen, IHOP and five Subway Sandwiches. There’s a Wal-Mart, and a Target just completed, and a place lined out on the city wish list for a Costco.

They say that the views from Wasilla are spectacular—views that were shrouded by clouds the day I passed through. These views redeem the city, they’ll tell you, and justify anyone wanting to settle there. But seen as I saw it, manmade, without the god-given backdrop, Wasilla is characterless, lacking any sense of place. Besides, Alaska is a state where spectacular vistas are commonplace, and seen without its view, Wasilla could be anywhere in rural America, indistinguishable from any other wide spot in the road where traffic slows, or stops to get gas or a drive-through burger. Palin and the media has spun the town as quintessentially America, the archetypical small town. And perhaps it is—but that is a comment on the sad state of rural America, not a recommendation for soulless suburban sprawl.

Dusk comes early up there in November and as the frail light dimmed that day the clouds turned to rain. There was no view of Denali.

I turned around at the northern end of the valley, at Talkeetna, a bustling wooden town with buckboard sidewalks and narrow planks crossing the streets turned by the rain into a wallow of mud. People chatted around the wood-burning stove in the old general store. There is really nothing else to do in Talkeetna that time of year; it’s cold and dreary, there’s no Wal-Mart or Blockbuster Video, and you have to trek the seventy miles to Wasilla if you want fast food. I had no reason to stay but I didn’t want to leave.

It was dark when I reached Wasilla on my way back to Anchorage. I stopped for gas then passed on through.

Wonder Valley

07 Jul 2010 3 Comments

by William Hillyard in Published Stories, Wonder Valley Tags: Amboy Road, Best American Nonrequired Reading, Bill Hillyard, Cat Ranch, Denver Voice, German Artist, jackrabbit homesteads, Joshua Tree, Literary Journalism, Mojave Desert, Narrative nonfiction, Ned Bray, Photojournalism, Preston drake-hillyard, Raub McCartney, Ricka McGuire, Route 66, small tract homestead act, The Palms, Tom Ritchie, Twentynine Palms, UCR Palm Desert, Whitefeather, William Hillyard, Wonder Valley

Below are links to the first four Wonder Valley stories. They are meant to be read as a piece…

Wonder Valley The first in the series. It introduces the place as it explores the life and death of one of the residents. The story was listed as “Notable Nonrequired Reading” in The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2010

Laying Tracks with Jack McConaha Travel the dirt roads of Wonder Valley with the area’s self-appointed guardian.

Falling to Heaven The lives of two men intersect in the loneliness and isolation of Wonder Valley

The People Vs Thomas Ritchie Busted at the Cat Ranch, a man fights felony charges while struggling to survive.

City of Cast-Offs

22 Mar 2010 Leave a comment

by William Hillyard in Published Stories, Tijuana Tags: Bill Hillyard, Colonia Chilpancingo, Colonia Nueva Esperanza, Earth Island Journal, globalization, Guillermo Arias, Literary Journalism, paracaidistas, Photojournalism, Tijuana, Tijuana River, William Hillyard

Tijuana is made of tires. Car tires. It is constructed of them: they form the walls of houses, shore up embankments, stabilize slopes, create retaining walls, staircases, curbs, fences, planters. Tijuana is awash in tires, buried under them. The tires all came from California originally; we export more than two million old tires to Mexico every year as part of a recycling program overseen by the state. Tire recycling means nothing more than relocating, it seems, exporting our problem to the other side of the international fence.

This is a short piece I wrote to accompany a photo essay by World Press Photo award-winning photographer Guillermo Arias. It appeared in the Earth Island Journal. Our assignment was to explore recycling: how does it fare as our first response to the American culture of consumption?

“Jorge Lopez works shirtless among a mountain of wooden pallets along the cluttered banks of Tijuana’s swampy Arroyo Alamar. He stacks the best pallets to one side and busts others into boards, piling them alongside the broken scraps gathered as firewood. Lopez makes his living selling the pallets, the boards, and the firewood to the squatters who live on the opposite bank of the arroyo. A whole pallet goes for two pesos — about 15 cents.”

Read the entire story: City of Cast-Offs

William Hillyard

Where is Away?

11 Dec 2009 Leave a comment

by William Hillyard in Published Stories, Tijuana Tags: Bill Hillyard, Colonia Chilpancingo, Colonia Nueva Esperanza, Denver Voice, globalization, Guillermo Arias, Illegal Immigrants, Literary Journalism, paracaidistas, Tijuana, Tijuana River, William Hillyard

“When ‘off-shore’ is Tijuana, just the other side of a rusty metal border fence, there is little to prevent the problems we send away from flowing back north.”

I got the idea for this story standing on the San Diego side of the border fence watching people squeeze north between the jagged stakes to have their picture taken. It seemed to me that the fence only kept out those who were willing to be kept out. The photos are by award-winning Tijuana-based photographer Guillermo Arias.

“At low tide, you could walk to Mexico, around the crusty palisade of the border fence, without even getting your shoes wet. The thinnest can slip between the stakes, as kids do, dashing into America—‘look at me, mom!’—and slipping back again over the line. The Pacific’s relentless waves and salt spray have long ago eaten the fence’s metallic flesh, leaving a disheveled skeleton of rusty spikes, 12 feet tall, like the broken and bent teeth of a giant scaly comb.” Read the entire story

Visit the Denver Voice archives HERE

William Hillyard

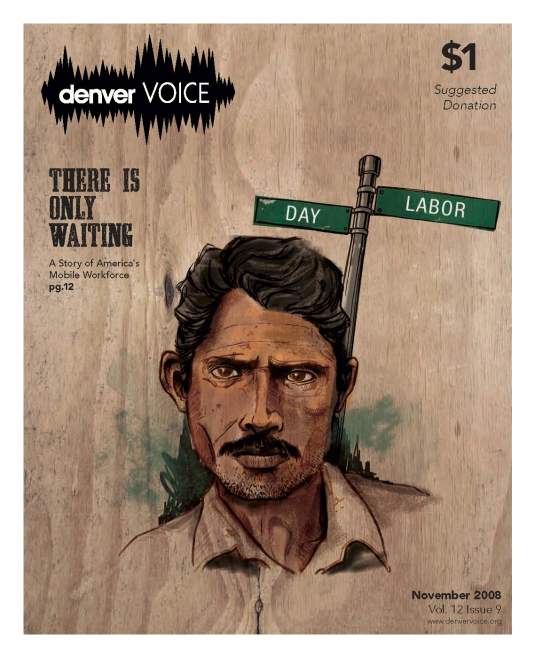

There is Only Waiting

21 Aug 2009 Leave a comment

by William Hillyard in Day Laborers, Published Stories Tags: Bill Hillyard, Day Labor, Denver Voice, illegal immigrant, Lake Forest, Literary Journalism, Pichoneros, William Hillyard

Denver Voice, November 2008

This story examines the relationship between undocumented day laborers and the Lake Forest, California community in which they live. It appeared in the November 2008 issue of the Denver Voice.

“Wedged between the railroad tracks and busy El Toro Road, bound by auto repair shops and a lumberyard, near the now vacant nursery with the dead potted trees and rented security fence, Orange Avenue meets Jeronimo Road…” Read the entire story

Visit the Denver Voice archives HERE

William Hillyard

Pichoneros

27 Jul 2009 Leave a comment

by William Hillyard in Day Laborers, Published Stories Tags: Bill Hillyard, Capistrano Beach, Dana Point, Day Labor, Denver Voice, globalization, illegal immigrant, Illegal Immigrants, jornaleros, Literary Journalism, NASNA, NASNA Award Finalist, North American Street Newspaper Association, Photojournalism, Pichoneros, Preston drake-hillyard, William Hillyard

“Pichoneros” are what the day laborers who hang out along Camino Capistrano in Dana Point, California call themselves. They liken themselves to pigeons (pichon is pigeon in Spanish), scratching their livelihoods from the dirt. This story looks at the pichoneros who, as the economy falters, find it harder and harder to survive. And many contemplate returning to Mexico, a place some have not called home for decades. This story was a finalist for the 2010 NASNA Best Feature Award.

“Patti Church eased her car around the corner and into the swirling crowd, stopping near the piles of clothing spilling from ripped plastic trash bags. Flimsy folding tables stood waiting for her. As Patti opened her car door, she became the center of the crowd; volunteers looked to her for direction, asking questions—where do you want this, who is to do that? One man, his face bristling with a silver stubble, opened Patti’s trunk and began unloading paper grocery bags to the folding tables, others grabbed cases of soda, boxes of cakes, plastic trays of salads, until the wobbly tables were top-heavy with food. Another, Francisco, grabbed a box from the car’s back seat, then stood shuffling from foot to foot, looking for an opening to the tables. As Patti approached, about fifty men, their weathered hands warmed in worn pockets, congealed into a tight group…” Read the entire article

Visit the Denver Voice archives HERE

William Hillyard

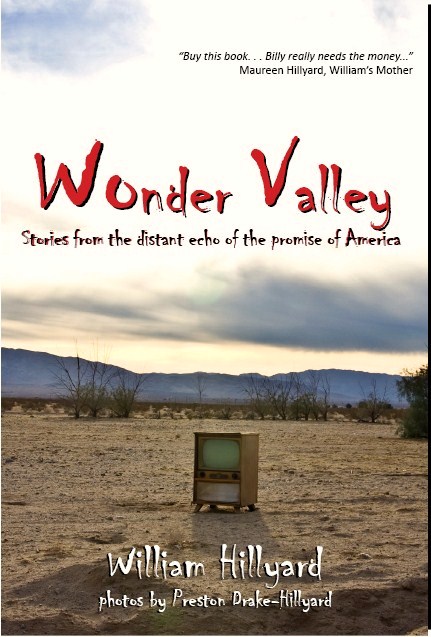

Wonder Valley by William Hillyard

16 Jul 2009 1 Comment

by William Hillyard in Published Stories, Wonder Valley Tags: Best American Nonrequired Reading, Bill Hillyard, Denver Voice, jackrabbit homesteads, Joshua Tree, Literary Journalism, Ned Bray, Photojournalism, Preston drake-hillyard, Raub McCartney, Ricka McGuire, small tract homestead act, The Palms, Tom Ritchie, Twentynine Palms, Whitefeather, William Hillyard, Wonder Valley

Ned Bray's Wonder Valley Parcel--photo by William Hillyard

Below is a link to my story on Wonder Valley which appears in the July issue of the Denver Voice. It is the first of what will be a series of stories on Wonder Valley, one of the last homestead tracts in the United States. It’s a strange place, dotted with tumble-down shacks it is peopled by an diverse mix of artists and retirees, losers and lowlifes, drunks and druggies, eccentrics and out-right wackjobs. This story was listed as “Notable Nonrequired Reading” in The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2010

“You might have passed through here, maybe. Out for a drive with time on your hands, you might have taken the long-cut to the casinos of Laughlin, Nevada from the soulless sprawl of Los Angeles. You’d have driven way beyond the outer reaches of suburbia, beyond its neglected fringe of citrus groves, past the outlet malls and the Indian casino, past remote Joshua Tree National Park and the Twentynine Palms Desert Combat Center, past the Next Services 100 Miles sign and any reason anybody really drives out this way…” Read the Entire Story

Check out more Wonder Valley photos HERE

Visit the Denver Voice archives HERE

William Hillyard